Civil Rights ≠ Standardized Testing

Mark Naison, professor of African American Studies and History at Fordham University, and a prominent voice in the fight for public education and civil rights, posted the following note on January 18, 2015 on Facebook and on his blog WithaBrooklynAccent.blogspot.com: “Do We Need to Redefine Civil Rights for Students”. In this note, he questions the beliefs behind the 19 civil rights’ groups who have recently endorsed national standardized testing. He believes that these groups are misguided, have misunderstood what the true inequality issues in schools are, and that these groups have been influenced, perhaps even bought out, by corporate funds and corporate propaganda.

Mark Naison, professor of African American Studies and History at Fordham University, and a prominent voice in the fight for public education and civil rights, posted the following note on January 18, 2015 on Facebook and on his blog WithaBrooklynAccent.blogspot.com: “Do We Need to Redefine Civil Rights for Students”. In this note, he questions the beliefs behind the 19 civil rights’ groups who have recently endorsed national standardized testing. He believes that these groups are misguided, have misunderstood what the true inequality issues in schools are, and that these groups have been influenced, perhaps even bought out, by corporate funds and corporate propaganda.

The discussion that follows his post on Facebook, both about standardized testing and about civil rights (and the defining/redefining of terms) leads me to seek out other voices, to see what they have to say.

Ravitch asks two questions in her one-paragraph rebuttal. “After 13 years of federally mandated annual testing, how could anyone still believe that testing will improve instruction and close achievement gaps?” and “How can one look at the results of Common Core testing in Néw York—where 97% of English learners, 95% of children with disabilities, and more than 80% of black and Hispanic students failed to meet the standard of “proficiency”—and conclude that these children are well-served by standardized testing?” The modality of the helping verbs (could = epistemic modality, expressing judgment of the truth; can = dynamic modality, expressing possibility and ability) forces the reader to agree with her strong stance. The answer to her questions is “no one could” and “no one can.” She eliminates all possibility of argument with her questioning strategy. In addition, she personifies the statement issued by the civil rights groups, (The statement makes assumptions) and she also personifies the tests themselves (Tests measure achievement gaps, they don’t close them.). This personification gives the statement and the tests a life-force, beyond the force of the authorship of the statement and the tests. The statement and the tests they support engender inequality. Most interesting to me, however, is the shortest sentence in the paragraph, almost dead center. “It never closes.” This three-word sentence finishes her explanation of a bell curve This sentence, however, is about more than a bell curve: it’s about the entire achievement gap and the mirroring gap in socioeconomic status and opportunity. It never closes. Syntactically, this sentence stands out for being the shortest, and for being positioned in the center. It expresses an absolute: never. It is the pinnacle statement of her argument, found at the center of it.

I am a Ravitch fan.

It is time to unpack what ideology is present in a news piece that is not overtly meant to preach to my choir.

The first paragraph states: “A coalition of civil rights groups released a statement Sunday urging Congress to maintain one of the most controversial portions of the federal education law known as No Child Left Behind: the requirement that public schools administer annual standardized tests in math and reading.” In the explanation of the portion of NCLB after the colon, the verb “to require” has been nominalized, so that there is no direct action and therefore no direct object; there is also no agency requiring the tests; instead, there is simply a requirement that stands because of this law. This nominalization and removal of controversy is in direct conflict with the declarative sentence before the colon, stating that this portion of the law is in fact “one of the most controversial portions.” The verbs used and the construction of the verbs provide both urgency and legitimacy to the civil rights groups’ position. They “released a statement” (as opposed to simply “stated”); the statement “urg[ed]” Congress; and Congress should “maintain,” signalling a status quo position.

The article continues: “The statement came the day before U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan was scheduled to stake out the same position in a speech at an elementary school in the District, highlighting a key battle line in the effort to rewrite the 2002 law.” The complicated verb structure removes responsibility from Arne Duncan. He “was scheduled” to “stake out” the same position. Some other agency scheduled him, giving him passivity in this scene. The metaphor, “to stake out” implies that he is not actually taking a position, but rather staking one out, as one would stake out a piece of property before they actually owned it, built a home on it, and lived on it. As this law was written in 2002, it is interesting that he would have to “stake out” the position that has been enacted in law for over a decade. If the law exists, and his position is to reenact the law, the implication that he was moving into new territory is a misnomer. This isn’t new territory. This is an old law. There is nothing to “stake out.”

The third paragraph states: “No Child Left Behind expired in 2007 and efforts to revise it have stalled on Capitol Hill. But Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.), a former U.S. education secretary who is now chairman of the Senate education committee, has pledged to move quickly to rewrite the measure. Alexander has said he is considering whether to jettison the exams, which are administered to students in grades three through eight and once in high school.” The word “jettison” in the second sentence is a very telling metaphor. To jettison is to drop cargo from a ship or plane, in order to lighten the load. A google search of this statement brings no clarity on if these words are a direct quote from Alexander, or if they are a paraphrase of his position. Regardless, the implication of considering whether or not to jettison the exams presents the idea that rewriting NCLB is a sinking ship, one which must be saved by the sacrifice of the exams.

In the fourth paragraph, Brown writes: “The testing requirement has come under fire from a strange-bedfellows movement of teachers unions, parents and conservative lawmakers who argue that the exams represent an overreach by the federal government that has turned schools into one-dimensional test-prep institutions. And tests do not address child poverty, which many critics of the legislation consider the root cause of continued achievement gaps between poor and affluent students.” The syntax of the second sentence creates ambiguity. Starting the sentence with the coordinating conjunction “and” implies that the sentence is a continuing thought from the previous sentence. However, the previous sentence discusses the “strange-bedfellows movement of teachers unions, parents, and conservative lawmakers” and their argument against the exams. It is not clear if the “strange-bedfellows movement” (a curious descriptor, first coined by Shakespeare in The Tempest...is this meant to be an allusion?) also argues that the tests do not address child poverty, or if this is the belief of Brown herself. The sentence structure causes the reader to attribute the poverty argument to the anti-testing movement, but the actual speaker of that belief is left unclear.

The article then quotes Kati Haycock, president of the Education Trust, who wrote: “Kids who are not tested end up not counting,” as an explanation of the position of the coalition of civil rights groups. In her statement, the kids are being acted on, thus underscoring the idea that the kids have no power. Another way to write this sentence is “Kids who do not take the test do not count,” which makes the kids active, not passive. However, as the civil rights groups are arguing that the implementation of the standardized tests and the subsequent “yawning achievement gaps” that these test scores have “unmasked” have “forced all states and school districts to focus on serving poor and minority students, including those with disabilities,” their argument that the tests are forcing states and schools to do right by students, needs to present the kids as being “acted on” and not acting. It is incredibly interesting that the civil rights groups believe that the testing has “unmasked yawning achievement gaps”; achievement gaps have not been hidden or secret. Standardized tests didn’t suddenly “unmask” them. Attributing the “unmasking” of the gaps to the tests ignores the decades of court cases leading up to and following Brown versus Board of Education. As a reader, I have to callously ask: do these civil rights groups not understand their own history?

The civil rights coalition also “wants Congress to continue requiring states to take action against schools that do not meet performance targets or close achievement gaps among groups of students.” Interestingly, Brown continues: “Under No Child Left Behind, such struggling schools have been subject to consequences ranging from firing staff members to closing and reopening as a charter school, actions that critics have said are overly punitive and disruptive and often do not improve student achievement.” This statement demonstrates transitivity and passive voice. The agency has been removed in this sentence and the staff members, schools, and student achievement have become objects, acted on by an unseen force. To change this to an active construction, Brown would have to write the following: “Staff members are fired in struggling schools. Schools are closed and reopened as charter schools. Student improvement does not improve when staff members are fired and schools are closed.” In the original sentence, all agency and ownership of the action is removed; it’s just “happening” under NCLB.

The article finishes with a list of things the coalition wants: pre-K access for poor children, and equal access to technology, alternate forms of discipline instead of suspension and expulsion, and a requirement that schools report how and when they involve the police and refer cases to the police. The article ends, almost as an afterthought, with the statement that the coalition takes no position on the using of student test scores in teacher evaluations.

Although Emma Brown does not blatantly state her position on NCLB or on the statement released by the civil rights coalition, she does show a lack of support for NCLB policy through her use of direct quotes, her juxtaposition of her statements following coalition statements, and her portrayal of the removal of agency. The coalition statements she uses highlights their misguided support of this very flawed law.

I am heartened to read Brown’s presentation of this topic. NCLB is flawed, and the current push for standardized testing is a travesty for our students and our schools. Brown has a platform on which to present to the public the information they need to have: that standardized testing does not help students, and the subsequent “reforms” brought about by the testing are harming the very students they are meant to help.

_______________________________________________________________________________

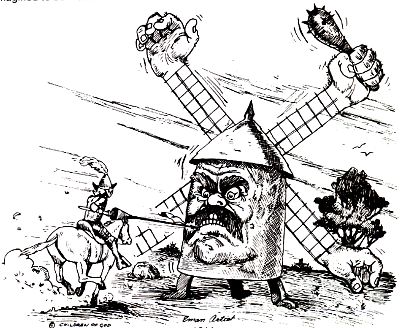

Graphic of Mark Naison used with permission.

...would still write for the Associated Press

...would still write for the Associated Press