...would still write for the Associated Press

...would still write for the Associated Press

Will Oremus, Slate’s senior technology writer, unpacks the idea of “automated journalism” in “Why Robot?”

“The Associated Press has been publishing corporate earnings reports written entirely by computer programs,” he states.

The primary focus of his piece is on the naming of the technology, and the different connotations that are presented with each name. He pushes back against the word “robot” as used by many writers he respects, writers who have written about robot journalists, robot-writing, and articles “written by a robot”.

“If I were a “robot” journalist,” he says,” I would deftly fill the rest of this post with updated facts and numbers describing the scope and pace of robo-journalism. Instead, my quixotic human brain has led me to focus on a question of semantics: Are the computer programs that are writing the AP’s news stories really robots? And if not, why do even the most careful of writers keep calling them that?”

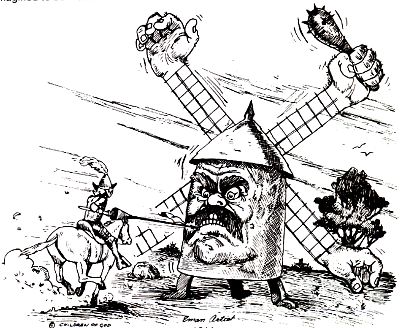

Obviously, we are to understand that Oremus, himself, is clearly not a robot. His use of the allusion to Don Quixote in his naming of his own brain identifies him as truly human, and full of the idealism, sentimentality, irrationality, and impracticality that separates the human from the machine. Oremus then sets out to idealistically, rationally, and practically (without sentimentality) analyze what this writing technology should be named, and why so many people are insisting on naming it what it is not.

Robbie Allen, the CEO of Automated Insights (the company behind this writing technology), calls it “software.” “It’s funny,” he says… “I mean, they know it’s all software, right?”

And yet Automated Insights has released the following video, clearly understanding in their PR department that this concept of “robot” is alive and kicking.

Oremus goes on to define for us what a robot truly is, including the history of the word and the current definitions of the word. He tells us that the word robot comes from the Czech word robota, meaning “forced labor.” It is “A machine capable of carrying out a complex series of actions automatically, especially one programmable by a computer.”

This article-writing program is not a machine, clearly. Therefore, it is logically not a robot. So what is it? Oremus asks leading industry experts for a better name.

Chris Anderson, co-founder and CEO of 3D Robotics and former editor-in-chief of Wired names this writing technology a bot: a software application that runs automated tasks over the Internet.

So Oremus goes back to Allen at Automated Insights and pushes for a better name. Allen comes up with “Automated Insights’ Wordsmith platform”...or...“a natural-language generation platform called Wordsmith.”

Oremus and Allen haggle it out and finally decide on the word software. “Software is writing AP stories,” Oremus finally declares.

So why, he asks, is everyone calling it a robot? What is it about this technology that makes us want to name it something other than software? His answer is two-fold. First, the name “robot” makes us click the link. When writers have to get readers, they have to get the readers to click; they get paid by the click. We all know what software is, and software is not sexy. It doesn’t get our heart racing. But a robot: a robot is an entity. And this is the second part of his answer. “The term carries a lot of pop-cultural baggage,” he states. His personification of the term, allowing it to carry emotional baggage, makes it an entity, just a little too close to being human.

In addition, the idea of a robot as an entity that can do what we humans do heightens the drama of us versus them. Robots will take our jobs. Robots will replace us. Robots will malfunction in some sort of Maximum Overdrive dystopia.

Oremus ends his piece juxtaposing the idea that this writing software has not, in fact, created a reduction in human staff at the Associated Press, but has opened up the writers to more creative projects, leaving the boring stuff to the software; and yet, he reminds us, we must be prepared for the change, for the elimination of jobs, and for the eventual rewriting of our roles.

Oremus’ insistence on finding an accurate and rational name for the AP writing software belies his warning at the end. He is, in fact, quixotic, both tilting at the robot windmill and simultaneously arguing that the windmill is simply misnamed. It seems that he has missed the point in using the obvious reference in the title of his piece “Why, Robot” to I, Robot, the Isaac Asimov short story collection. Asimov’s Three Laws state:

- A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

- A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings, except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

- A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

The naming of the technology may lessen or heighten our human emotional reactions to it; but the creation, control, and ethical use of the technology is and will continue to be up to the human beings who live with it.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments on this blog are moderated. I will approve on-topic and non-abusive comments. Thank you!